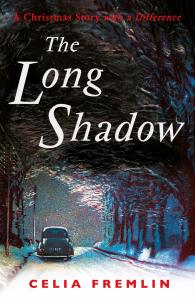

Celia Fremlin – The Long Shadow

I love novels that refuse to be pigeonholed into one single genre. After all, if you can have more than one treat in the same package, why not? And I admire authors who have the ability to straddle genres with ease, spicing up their narrative recipe with a mixed bag of ingredients.

I love novels that refuse to be pigeonholed into one single genre. After all, if you can have more than one treat in the same package, why not? And I admire authors who have the ability to straddle genres with ease, spicing up their narrative recipe with a mixed bag of ingredients.

Celia Fremlin has this ability in spades, and ‘The Long Shadow’ is a brilliant example of her skills. As well as being a tremendously entertaining story that’s part suspense novel, part social and psychological study, and 100% bursting with razor-sharp insight and cleverly crafted language.

Timing is everything in fiction, and the ‘The Long Shadow’ is built like clockwork. Fremlin doles out her story morsel by juicy morsel, each as captivating as the next, each finely balanced for dialogue and pace, each making the reader yearn for the next.

The plot is, at first glance, disarmingly simple: a distinguished middle-aged Classics professor, Ivor Barnicott, dies in a car accident in early autumn, and his grief-stricken third wife Imogen is left to deal with the aftermath, coping with a deluge of sympathetic relatives and friends, some of whom somehow wheedle themselves into spending Christmas at the Barnicott home, ostensibly to brighten up Imogen’s first widowed festivities.

The cast isn’t large but it’s varied: Imogen’s step-children, both in their early thirties, disturbingly unsensitive Robin and his control-freak sister Dot (with two small children and under-the-thumb husband Herbert in tow), both siblings seemingly endowed with a different streak of Ivor’s less-than-endearing character; Cynthia, Ivor’s second wife, whose vapid-woman act conceals a cunningly resourceful mind, and who installs herself unbidden in the house, under the guise of sharing Imogen’s sorrow; and Piggy, a young woman with unspecified boyfriend troubles and supposedly a friend of Robin’s, who becomes the household’s self-appointed lodger.

Having to cope with them all, as relative, friend and landlady, is Imogen: stricken but determined, equally allergic to condolences and complacency, both heartbroken for Ivor’s tragic, untimely death and eager to get out of the shadow cast by his passing away. And, as we gradually learn, the shadow cast by his relentless, unforgiving search for academic recognition.

Fremlin leaves the reader guessing as to which of these sentiments is prevalent in Imogen’s mind, and casually slips in a hint that she might possibly have had something to do with Ivor’s death – or so a mysterious caller suggests, pointing out how Imogen, even though notified about Ivor’s fatal accident by the hospital, kept the fact secret from everyone for twenty-four hours. As Imogen and her motley household prepare for Christmas, Fremlin unhurriedly but clinically plants the seeds of suspicion amidst the commonplace comings and goings of the daily lives of her characters.

Mercilessly exposing the small-scale savagery of family relationships is one of Fremlin’s fortes, hand-in-hand with the occasional wryly humorous barb, and the setting she creates is perfect for this: a large house, a family fraught with (mostly) unspoken attritions, and more and more facts about Ivor’s death, and Imogen’s supposed role in it, gradually emerging.

Like Fremlin’s other works, ‘The Long Shadow’ is not in any sense a conventional crime or thriller novel. Yet it has all the ingredients to generate suspense, to titillate the reader into wanting to know who is responsible for Ivor’s death, who could be bent on pinning it on Imogen, and why. And Fremlin is devilishly clever at keeping the who and why well-concealed until the novel’s surprising, dramatic finale.

Yet the setting is resolutely domestic, and there is none of the adrenalin usually associated with crime fiction: no violence, no police investigation, no detective or sleuth. In fact, there seems to be little or no physical danger for Imogen in the whole affair, be it violence or the threat of being arrested. But there are other kinds of danger involved. By slow accretion, Fremlin’s beautifully observed sketch of domestic life shows that perhaps the greatest danger Imogen faced was that of anonymity, and of subservience to the overpowering figure of the man in her life, both before and after his death.

Filled with an array of captivating female characters, ‘The Long Shadow’ clearly portrays the harshness of the choice some women face between a life of domesticity and one of independence. Even if the latter simply meant, for Imogen, a generic, though justified, yearning to get away from the long shadow of an overbearing, unpleasant man like Ivor, Fremlin shows how high a price she risks paying for it. A price which, for other characters in the novel – I can’t say who to avoid spoilers – is indeed tragically high.

I deliberately omitted to say that Celia Fremlin wrote in the second half of the 20th century: she published 19 novels between 1958 and 1995, each a deliciously sketched psychological scrutiny of middle-class life, and each containing more than one chilling, venomous twist. Even though she wrote some decades ago, her novels (Faber & Faber recently published also her first, ‘The Hours Before Dawn’, which won the Mystery Writers of America Edgar Award for Best Novel in 1960) are incredibly fresh and contemporary, in style and subject matter. Indeed, it’s sobering to think that, even in the 21st century, there are women who, like Imogen, have to pay a high price to live life on their own terms, and not under a man’s shadow.